From Doing to Being - The Lost Art of Doing Less

We live in a world addicted to doing. But what if the most powerful shift doesn’t come from doing more—but from doing… nothing?

We live in a world addicted to doing. But what if the most powerful shift doesn’t come from doing more—but from doing… nothing?

I just returned from a two month silent retreat - just me alone in a cabin for sixty days - and what I found might surprise you. This wasn’t a vacation or an escape. It was a deep dive into the mind, and into a form of meditation that doesn’t ask you to focus, fix, or improve. It asks you to rest. To be. And shifting from doing to being—it turns out—can change everything.

I. Returning to Retreat

Back when I was younger, I did long retreats every single year—usually at least a month, sometimes longer. The longest was five months of silent, dedicated meditation practice, where I was meditating 12 or more hours a day. That probably sounds unthinkable, maybe even unbearable. But for me, these periods of deep retreat have been the most transformative experiences of my life.

Even a half-day, or a weekend of space and stillness, can open a window into the mind that’s as powerful as years of daily practice.

But it's been a long time since I carved out this kind of space. When my son was born 20 years ago, I made a commitment that he would be my priority. So for all the years he was home, I kept retreats short—a week or two at most. Still, I never stopped dreaming about returning to longer practice. So when he went off to college, I did exactly what I'd been waiting to do: I scheduled a full two-month retreat.

II. What Kind of Meditation?

There are lots of ways to do retreat. Most of my practice has come from the Tibetan Buddhist tradition. These practices range from contemplations on impermanence, suffering, and compassion—to imaginative techniques that shift how we see ourselves and the world.

But my personal favorite is something much simpler, and maybe more mysterious: the practice of non-dual awareness.

“Non-dual awareness is a form of meditation that begins with a radical shift: from doing to being.”

Instead of trying to change or improve anything, you simply rest. Effortlessly. Awake. Open. Natural.

From this space of effortless presence, the mind begins to reveal itself—and sometimes, something deeper than the mind. These are practices designed to explore the nature of consciousness itself.

They’re hard to describe. But for centuries, they’ve been seen as the most profound teachings in the Tibetan tradition. And many other traditions point to similar experiences through different doors—Dzogchen, Mahamudra, Advaita Vedanta, even some mystical strands of Christianity and Sufism.

III. What Does It Mean to Do Nothing?

So what do you actually do on retreat, if you're not "doing" anything?

In this case, the answer was: not much. In fact, for the first week, I did a traditional practice where you literally sit and do nothing. You don’t focus on the breath. You don’t observe thoughts. You just sit. And rest.

To some, that might sound like a blissful vacation. To others, maybe like torture. Either way, I can promise you this: it's fascinating.

When you drop all effort to control your experience, the mind has a lot to say. For most of us, just a few minutes of stillness brings up a storm of thoughts. We ruminate about the past. We worry about the future. We fixate on what hurts or what's missing.

This tells you something. Doing nothing is not as easy as it sounds. But it is powerful. Because if you stick with it, you start to see the mind clearly. You learn something about your habits. Your reactions. Your stories. And maybe, just maybe, you begin to sense that there's more to who you are than all of that.

IV. The Science of Being

In the mid-2010s, researchers at the University of Virginia ran a now-famous experiment. They asked college students to sit quietly for just 6 to 15 minutes, alone with their thoughts—no phone, no book, nothing. Many participants found this so uncomfortable that they opted to give themselves mild electric shocks rather than sit still.

What’s happening here?

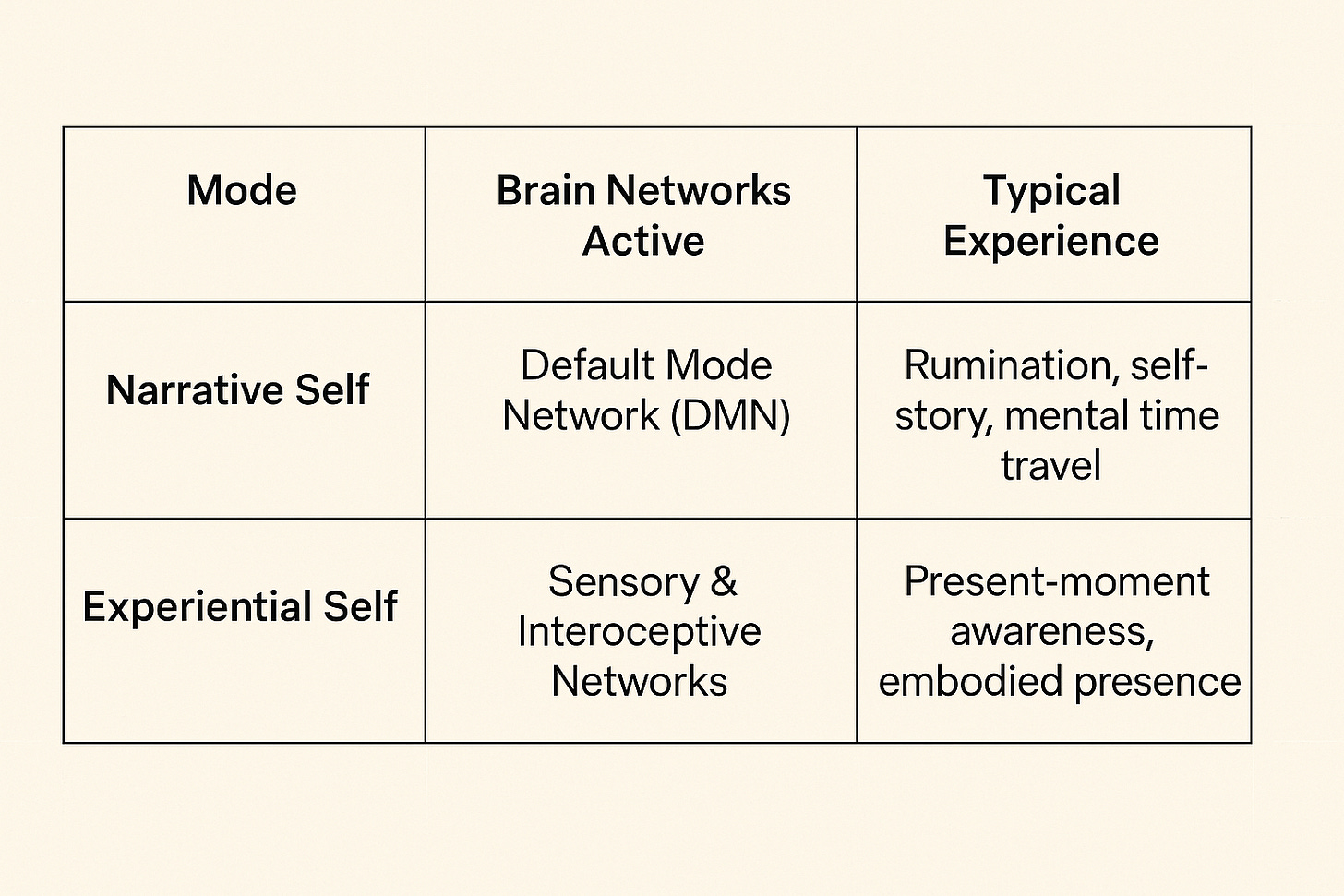

When the mind isn’t occupied, the brain’s default mode network (DMN) often springs into action. This network—linking regions like the medial prefrontal cortex and posterior cingulate cortex—is heavily involved in self-referential thinking: rehearsing past regrets, worrying about the future, and reinforcing a mental story of “me.”

That’s why doing nothing can feel agitating—it surfaces all the background chatter we usually keep at bay with constant activity and distraction.

But here’s where it gets interesting.

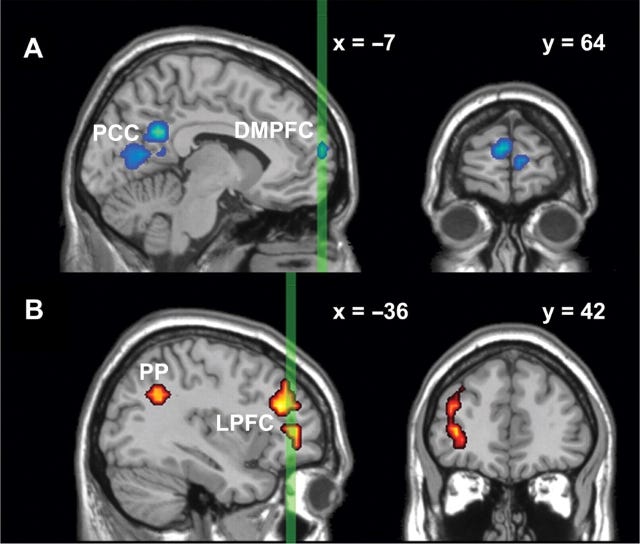

Research by Norm Farb at the University of Toronto—and others in contemplative neuroscience—has shown that when people practice being present, their brain activity shifts dramatically.

The DMN quiets down, meaning less rumination and narrative self-talk.

Activity increases in sensory and interoceptive networks—including the insula, which tracks internal bodily states like breath, heartbeat, and emotion.

This shift is sometimes described as moving from the narrative self to the experiential self—from thinking about life to directly experiencing it.

Even more remarkable: these changes aren’t just momentary, these are trainable skills. And as Richie often says, with sustained practice, they can become traits rather than fleeting states—meaning your brain learns to rest more naturally in awareness, even when you aren’t meditating.

(A) Areas of greater association with the Narrative condition (Narrative > Experiential) are in blue, and (B) areas of greater association with the Experiential condition (Experiential > Narrative focus) are in red.

V. The Culture of Doing

Most cultures, if not all, had daily rituals centered around being. But in the 21st century, we’ve largely erased these cultural rhythms and replaced them with compulsive and endless doing.

It still exists in some places. I lived for many years in the Himalayan foothills of Nepal amidst Tibetan refugee communities. There were a few times every day where everything would just stop, and people would sit around and drink a nice cup of tea. Sometimes in silence, sometimes in conversation. But always, it was a moment to forget the to-do list and unwind.

In Japan, too, you can find echoes of this—though increasingly, these are more cultural artifacts than living traditions. Tea ceremony. Calligraphy. Poetry. Even martial arts. These may look like forms of doing, but they are infused with a quality of being. They weave together effort and ease, action and awareness.

Here in the U.S., we’ve lost almost all of this. We have work lunches. We drink our coffee on the go. Even walking in nature is done with earbuds in, checking texts or listening to podcasts instead of taking in the beauty of our surroundings.

It has all slipped away so gradually that we barely noticed. And what’s left is a culture that’s forgotten how to simply exist without doing anything—a culture that confuses our value as human beings with our productivity.

V. The Skill of Being

Lucky for us, being tormented by our thoughts or losing ourselves in distraction are not the only options.

We can treat being like a skill. It’s something we can learn and practice.

So what does it actually mean to say that being is a practice? There are really three steps.

Step one: Effortlessness. This means letting go of the impulse to control whatever might be happening in your own mind. If you're a meditator, this probably goes against every shred of meditation training you've had—unless you've been trained in traditions that emphasize non-doing and effortless presence. The key to being is that you can't do it. It isn’t a practice in the usual sense, where you apply effort to reach a goal. This is something totally different. It’s a non-practice. A non-doing. You simply allow everything to unfold naturally. You don’t even control the movement of attention. You don’t need to focus on your breath, observe your mind, or stop thinking. You’re taking your foot off the gas, 100%.

Step two: Presence. This complements effortlessness. Presence isn’t about doing something to your mind. It’s about attuning to a quality that’s already here. You may not be in touch with awareness, but it's always with you. Always. This step is about tuning into that awareness—letting it move from background to foreground. You’re not making yourself more aware. You’re trusting in the presence of awareness and learning to be that awareness.

Step three: Naturalness. Here, the practice is pure allowing. Unconditional and radical openness. Most of us move toward pleasant experiences and away from painful ones—but here, we let everything be. A calm mind, a chaotic mind—it doesn’t matter. You let it be. Like the classic sky-and-clouds analogy: the weather changes, but the sky remains. Awareness is like that—open, peaceful, and accommodating. Nothing can harm it. With naturalness, we rest as the sky and let the weather be what it is.

Together, these three steps—effortlessness, presence, and naturalness—are the heart of the lost art of being.

Practice Prompt: 3 Ways to Shift into Being

You don't need to do months of retreat to practice this skill. One moment is enough. Here are a few simple ways to get started.

Pause Between Tasks. Even a 90-second reset between meetings or a few breaths before bed can rewire your nervous system. Feel free to do a short meditation right now (below meditation link). Take a short break and finish reading the post. How does that make you feel?

Practice open awareness. Set aside 5–20 minutes to rest in effortless presence. Let go of focusing, fixing, or controlling. Just be.

Try “being” on the go. Bring effortless presence into movement—walking, talking, driving. Doing can happen within being. That shift is profound. Allow your mind to drop into a state of effortless presence while your body is getting stuff done. It takes practice, but it's a total game-changer.

VI. What I Found in the Stillness

So, back to my retreat.

That first week of doing absolutely nothing led me through some surprising inner terrain.

Old memories surfaced. Emotional patterns I didn’t even know were buried came up and released. I experienced a level of inner peace and rest that was profoundly healing.

Most of all, I began to reconnect with something deeper—a sense of being that shifted how I see myself and the world.

It might sound abstract. And yes, it is. But it’s also real. And when it lands, it can move you to tears.

You don’t need months of retreat to find it. Just a little space. A little trust. And a willingness to remember:

Our value doesn’t come from what we do. It comes from who we are.

And this is something you can discover for yourself. It just takes practice.

Warmly,

Cort

Reference Notes:

Check out this longer 5 minute meditation for free on Open Awareness. This was created for Healthy Minds Innovations, a non-profit founded by Richie in Madison, WI.

In case you missed it this week, check out our post and podcast, covering “Your Brain on AI”:

Post:

Podcast:

Thanks so much for your wisdom. Resonating totally. I love being on silent retreats. An occasion to connect with something deeper inside. A precious opportunity to experience the mind and beyond. I came back from a week of silence retreat. So precious. Now bringing the wisdom into everyday life🫶🤩

Many thanks to Cort for this illuminating personal description of practice. It fits Zen/Zazen/Shikantaza in the Japanese Soto Zen tradition that I have studied, practiced, and taught in over the last sixty years--introduced to me by Shunryu Suzuki Roshi in the Sixties. It was his inspiration that led a few of us to bring Dainin Katagiri Roshi to Minneapolis in 1973 to found the Minnesota Zen Center (still thriving on the eastern shore of Bde Maka Ska). I like to describe this practice in plain Americanese as "the meditation of no assignment"--nothing to do, as Gautama reportedly said he did during Monsoon in India, but to know each breath, the body, and the mind as all arises. No assigned Koans, no visualizations, no mantras, etc. (all good on their own terms). I've been familiar with Richie's work (especially the early scientific papers with Jon Kabat-Zinn) for some 25 years, starting when I developed and taught credit-bearing meditation and mindfulness courses at the Bakken Center at the U. of Minn--with Jon K-Z's generous cooperation to insure that we mirrored his eight-week MBSR protocol.

Erik F. Storlie, PhD